CJ Cherryh’s long-running Foreigner series has a lot of interesting linguistics in it. One of her specialties is writing non-human species (or post-human, in the case of Cyteen) with an almost anthropological bent. Whenever people ask for “social-science fiction,” she’s the second person I recommend (Le Guin being first). These stories usually involve intercultural communication and its perils and pitfalls, which is one aspect of sociolinguistics. It covers a variety of areas and interactions, from things like international business relationships to domestic relations among families. Feminist linguistics is often part of this branch: studying the sociology around speech used by and about women and marginalized people.

In Foreigner, the breakdown of intercultural communication manifests itself in a war between the native atevi and the humans, who just don’t understand why the humanoid atevi don’t have the same feelings.

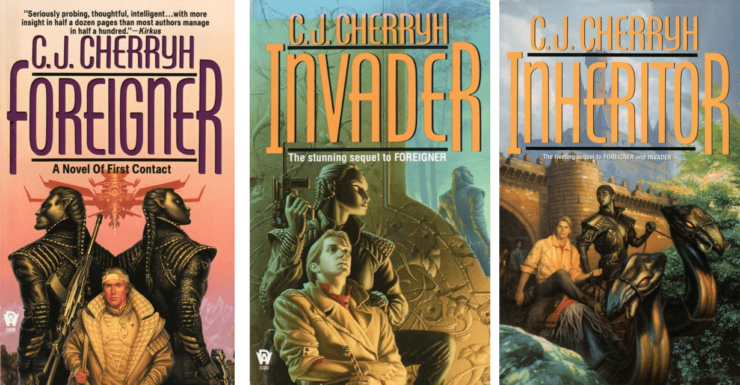

The first trilogy of (currently) seven comprises Foreigner, Invader, and Inheritor, originally published from 1994-96. It opens with a human FTL ship missing its target and coming out of folded space at a white star that isn’t on any of their charts. The pilots and navigators find a more hospitable destination and after some time spent refueling, they head there. Once they reach this star, they find a planet that bears intelligent life—a species that has developed steam-powered engines and rail. Some of the humans want to drop to the planet and live there instead of in the space station, while others want to stay on the station and support the ship as it goes searching for the lost human stars.

A determined group of scientists build parachute capsules and launch themselves at an island that looks less densely occupied than the mainland, where they build a science station and start studying the planet’s flora and fauna. At one point, an ateva encounters a human and essentially kidnaps him to find out why they are on his planet and what they’re doing. This initiates a relationship between two species who each assume the other is biologically and psychologically like they are. Humans anthropomorphize everything from pets to Mars rovers, so why wouldn’t we project ourselves onto humanoid species from another planet?

Atevi are psychologically a herd species. They have a feeling of man’chi (which is not friendship or love) toward atevi higher than themselves in the hierarchy, and they associate themselves (again, not friendship) with other atevi based on their man’chi. Humans, not understanding this basic fact of atevi society, create associations across lines of man’chi because they like and trust (neither of which atevi are wired for) these atevi who have man’chi toward different (often rival) houses. This destabilizes atevi society and results in the War of the Landing, which the atevi win resoundingly. Humans are confined to the island of Mospheira, and they are allowed one representative to the atevi, the paidhi, who serves both as intercultural translator and as intermediary of technology. The humans want to build a space shuttle to get back up to the station, you see, and they need an industrial base to do so. Which means getting the tech to the atevi—who, in addition, have a highly numerological philosophy of the universe, and thus need to incorporate the human designs and their numbers into their worldview and make them felicitous.

With this background, the real story opens about two hundred years later with a focus on Bren Cameron, paidhi to the current leader of the Western Association of atevi, Tabini-aiji. Unbeknownst to Bren, the ship has returned to the station, which threatens to upset the delicate human-atevi balance—and forces the space program to accelerate quickly, abandoning the heavy lift rockets already being designed and shifting to the design and production of shuttlecraft. This exacerbates existing problems within atevi politics, which are, in human eyes, very complicated because they don’t understand man’chi.

Throughout, I will refer to “the atevi language,” but Bren refers to dialects and other atevi languages than the one he knows and which the atevi in the Western Association speak, which is called Ragi. Atevi are numerologists; the numbers of a group, of a design, of a set of grammatical plurals, must be felicitous. This necessitates an excellent mathematical ability, which atevi have. Humans don’t, but with enough practice, they can learn.

Bren’s attempts to communicate with the atevi using terms he understands only imperfectly, because they don’t relate perfectly to human psychology, are an excellent example of how intercultural communication can succeed and break down, and how much work one has to do to succeed. Bren frequently says that he “likes” Tabini and other atevi, like Tabini’s grandmother Ilisidi and Bren’s security guards Banichi and Jago. But in the atevi language, “like” is not something you can do with people, only things. This leads to a running joke that Banichi is a salad, and his beleaguered atevi associates put up with the silly human’s strange emotions.

When the ship drops two more people, at Tabini’s request, one heads to the island of Mospheira to act as representative to the human government, and the other stays on the mainland to represent the ship’s interests to the atevi and vice versa. Jason Graham, the ship-paidhi, gets a crash course in the atevi language and culture while adapting to life on a planet, which is itself a challenge. He has no concept of a culture outside of the ship, or that a culture could be different from his own, and he struggles with atevi propriety and with Bren, who is himself struggling to teach Jase these things.

Buy the Book

A Psalm for the Wild-Built

One of the things Bren tries to pound into Jase’s head is that the atevi have a vastly different hierarchy than humans, and the felicitous and infelicitous modes are critically important. Bren thinks, “Damn some influential person to hell in Mosphei’ and it was, situationally at least, polite conversation. Speak to an atevi of like degree in an infelicitous mode and you’d ill-wished him in far stronger, far more offensive terms”—and may find yourself assassinated.

Even the cultures of the ship and Mospheira are different, because life on a ship is much more regimented than life on a planet. Jase likes to wake at the exact same time each day and eat breakfast at the exact same time each day, because it’s what he’s used to. Bren thinks it’s weird, but since it’s not harming anyone, he shrugs it off. Their languages are similar, because they’re both working primarily from the same written and audio records, which “slow linguistic drift, but the vastly different experience of our populations is going to accelerate it. [Bren] can’t be sure [he’ll] understand all the nuances. Meanings change far more than syntax.” This is, broadly speaking, true. Take the word awesome, which historically means “inspiring awe,” but for the last forty years or so has meant “very good, very cool .”

The ship has been gone for around 200 years, which is equivalent to the period from today in 2020 to the early 1800s. We can still largely read texts from that time, and even earlier—Shakespeare wrote 400 years ago, and we can still understand it, albeit with annotations for the dirty jokes. On the other hand, the shift from Old to Middle English took a hundred years or so, and syntax, morphology, and vocabulary changed extensively in that period. But because we can assume that the ship wasn’t invaded by the Norman French while they were out exploring, it’s safe to assume that Bren and Jase are looking at a difference more like that between Jane Austen and today than between Beowulf and Chaucer.

When Jase hits a point where words don’t come in any language because his brain is basically rewiring itself, I felt that in my bones. I don’t know if there’s scientific evidence or explanation for it, but I’ve been there, and I’d wager most anyone who’s been in an immersive situation (especially at a point where you’re about to make a breakthrough in your fluency) has, too. It’s a scary feeling, this complete mental white-out, where suddenly nothing makes sense and you can’t communicate because the words are stuck. Fortunately for Jase, Bren understands what’s happening, because he went through it himself, and he doesn’t push Jase at that moment.

When Jase has some trouble with irregular verbs, Bren explains that this is because “common verbs wear out. They lose pieces over the centuries. People patch them. […] If only professors use a verb, it remains unchanged forever.” I had to stop on that one and work out why I had an immediate “weeeelllllll” reaction, because I wrote my thesis on irregular verbs in German, and data in the Germanic languages suggests the opposite: the least-frequently-used strong verbs are the most likely to become weak, because we just don’t have the data in our memories. On top of that, a lot of the strong and the most irregular verbs stay that way because they’re in frequent (constant) use: to be, to have, to see, to eat, to drink. We do have some fossilized phrases, which Joan Bybee calls “prefabs,” that reflect older stages of English: “Here lies Billy the Kid” keeps the verb-second structure that was in flux in the late Old English period, for example. The one verb that does hew to this is to have. I/you/we/they have, she has; then past tense is had. This is a weak verb, and, strictly following that rule, it would be she haves and we haved. But clearly it isn’t. This verb is so frequently used that sound change happened to it. It’s more easily seen in German (habe, hast, hat, haben, habt, haben; hatte-), and Damaris Nübling wrote extensively about this process of “irregularization” in 2000.

Atevi culture, not being the (assumed Anglophone) human culture, has different idioms. Here are some of my favorites:

- “the beast under dispute will already be stewed”: a decision that will take too long to make

- “she will see herself eaten without salt” because of naïvete: one’s enemies will get one very quickly

- “offer the man dessert” (the next dish after the fatal revelation at dinner): to put the shoe on the other foot

So! What do you all think about the plausibility of a language that relies on complex numerology? Do you think the sociological aspects of the setting make sense? Are you also a little tired, by the time we get to Book 3, of the constant beat of “atevi aren’t human, Bren; Banichi can’t like you, deal with it”? Let us know in the comments!

And tune in next time for a look at Cherryh’s second Foreigner trilogy: Bren goes to space and has to do first contact with another species and mediate between them and the atevi, too! How many cultures can one overwhelmed human interpret between?

CD Covington has masters degrees in German and Linguistics, likes science fiction and roller derby, and misses having a cat. She is a graduate of Viable Paradise 17 and has published short stories in anthologies, most recently the story “Debridement” in Survivor, edited by Mary Anne Mohanraj and J.J. Pionke. You can find her current project, a book on practical linguistics for writers, on Patreon.